What is Galvanic Corrosion?

Galvanic corrosion (also called ‘ dissimilar metal corrosion’ ) refers to corrosion damage induced when two dissimilar materials are coupled in a corrosive electrolyte. However, it can also occur when the two metals touch or come into contact with each other. One metal acts as the ‘Anode’ and the other as the ‘Cathode’. When a galvanic couple occurs, one of the metals in the duo becomes the anode and corrodes faster than it would all by itself, while the other becomes the cathode and corrodes slower than it would alone.

With antenna manufacturing, the most common galvanic corrosion occurs between the aluminium [anode]; the normal stock used for elements] and the stainless steel fittings [cathode] such as worm drive clamps and nuts, bolts and washers that hold the element structures together.

I’m sure you’ve all seen it before. White corrosion particles and crud around a join on aluminium, where a stainless steel bolt/nut and washer have been used and left untreated over time.

The amount of corrosion which occurs depends greatly on where the metal sits in the nobility table. The amount of corrosion is a potential difference between the different materials and an electrolyte. The normal electrolyte would be rain water although operators located close to the sea will be affected differently by the addition of salt in the water. The bimetallic driving force was discovered in the late part of the eighteenth century by Luigi Galvani and is the building blocks of battery technology.

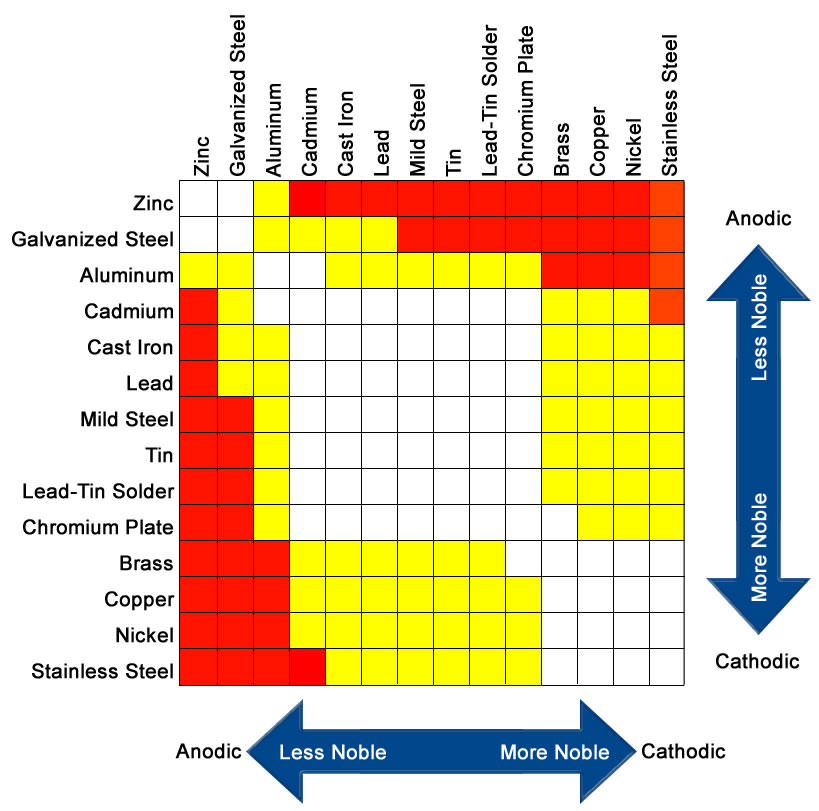

With similar metals coming into contact with each other, this process does not normally occur. The table below shows white, yellow and red squares. The white squares show metals that are normally compatible with each other and as such, galvanic corrosion is unlikely to occur. Metals that fall into the yellow boxes can potentially have some minor corrosion issues. Metals that fall into the ‘Red’ boxes are highly dissimilar and galvanic corrosion will occur – just like when you bolt through an aluminium tube with a stainless nut and and bolt. Leave it a year and there’s plenty of white ‘crud’ around the join. That’s basically the stainless steel dissolving the aluminium.

You can easily see that ‘Stainless Steel’ and ‘Aluminium’ are about as far apart as they can be on the below table

Others [Aluminium and Stainless Steel for example] – a potential difference exists between them.

How do you prevent Galvanic Corrosion?

We found the easiest way was to coat the two metals with some form of protection. Short term, sprays such as ‘WD40’ would go a long way to prevent it but longer term we found compounds such as ‘Alumslip‘ [manufactured by Molyslip] much more suited to working with antennas.

Alumslip [Which is similar to ‘Copaslip‘ and used on vehicle brakes] – works very well over a longer period of time and a slither of this will keep ‘GC’ away from your installation. We would warn you though, it’s extremely mucky stuff to work with and you don’t need much of it.

.